The Love Story of David Chang

Text by Euno Lee

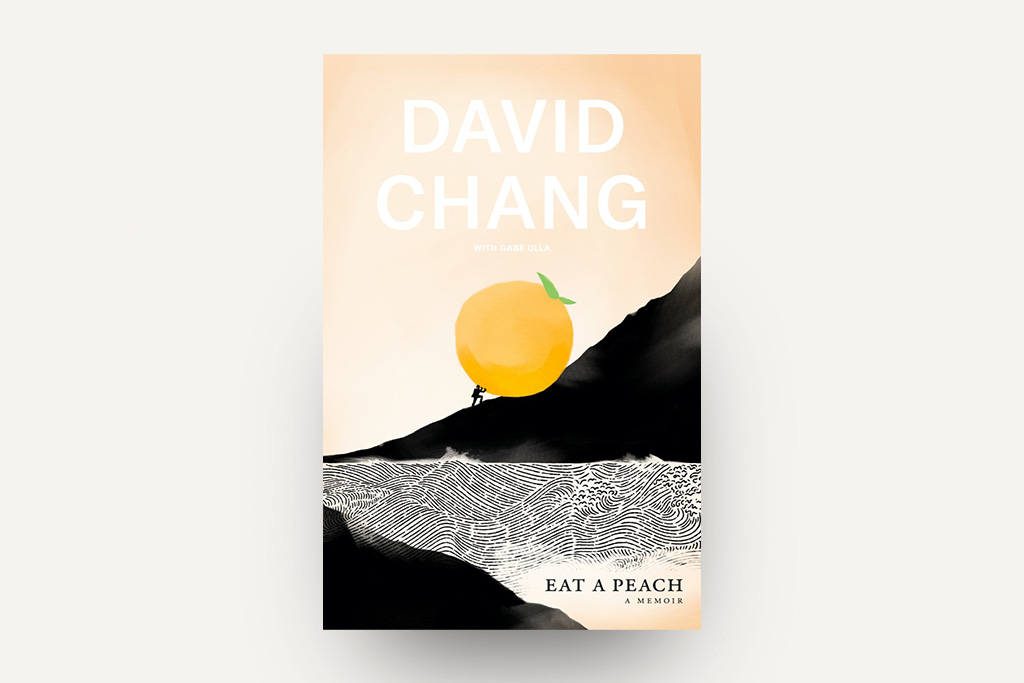

One would think that for growing up in a Virginia suburb and becoming the host of the Emmy-nominated Netflix show Ugly Delicious, founder of the international empire of Momofuku restaurants, and winner of countless James Beard Foundation Awards, David Chang’s memoir “Eat a Peach” should be a straightforward affair.

“If you work hard enough, you can achieve the American Dream,” it should imply. Chang will describe how he pulled himself up from his bootstraps, a rags-to-riches victory lap to cash in on his massive cult of food culture navel-gazers. The critics will fawn (as they seem to do with virtually anything Chang does these days). It will invoke standard-issue memoir adjectives like “inspiring,” and “courageous.”

Except the memoir doesn’t do any of this. There isn’t much to celebrate in the fast-turning pages of “Eat a Peach”. It is a recounting of Chang’s countless personal failures with just enough detail so that the “American Dream” can be conjured up just this side of corporeal — only for that Dream to be crushed into oblivion by a hurricane of rage, abuse and self-loathing. Chang treats his success as not something achieved, but rather something that somehow managed to escape.

The memoir limps to a start with the image of an eight-year-old Chang crying as he attempts to walk with a fractured femur to live up to his father’s expectations. Without explicitly stating it, Chang reveals that as a child he is taught love is conditional — something meted out commensurate with accomplishments, which in turn is just meeting expectations.

The memoir stews in this stifling haze of childhood abuse and conditional love from his parents, and explores how his childhood has led to analogous behavior on Chang’s part in his journey to the top of one of the world’s most demanding professions. The inference drawn from childhood abuse to Chang’s vignettes of personal failures is one of “Eat a Peach’s” more focused (and convincing) themes. And that list of personal failures is a long one — from coping with the death of a worker under his employ, to struggling with mental illness, to extremely detailed accounts of his infamous tirades.

The self-flagellating tone dampens even Chang’s greatest triumphs. The chef downplays critical moments that formed the fulcrums of the Momofuku machine — including one stunning instance involving a building permit — as dumb luck. The ever-cerebral chef presents his accomplishments not in relief of sweat-soaked toques and sleepless nights, but as a series of completely irrational statistical aberrations.

However, therein lies the magic of Chang’s charisma — the suggestion that none of his success is a direct result of his hard work at all, but simply good fortune. At the heart of what makes Chang so likable to the public at large is not his enjoyment of this good fortune, but rather the blank stare he wears in the face of it that seems to say, “Listen, I have no idea how this happened, either.”

A deeper reading reveals Chang grapples with the morality of success in retrospect. Perhaps what’s alluded to in the book’s cover art is that he has discovered something resembling joy in the Sisyphean process of chasing critical acclaim and accomplishments, only to then publicly downplay them or assign due credit to others to diminish the power of accomplishments over him. In essence, devaluing the currency exchanged for the conditional love he experienced in childhood.

Speaking of the cover, not enough is made of the memoir’s title — an allusion to a line from poet T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Throughout the poem, Eliot’s titular protagonist is paralyzed by fear and indecision about how to approach a woman, his self-consciousness and fear of rejection leading to an internal inventory of minute decisions (“Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?”).

In March 2019, Chang’s wife Grace gave birth to the couple’s son, Hugo. In the memoir’s final pages, Chang describes the moment of his son’s birth as feeling at peace. Chang attempts to reconcile with his father both in his life as David Chang, the son, and in the text as David Chang, the memoir’s protagonist.

And perhaps the truest resolution of the memoir’s tension comes in the act of publishing the memoir itself, and its implications for David Chang, the person. Chang confronts his demons of abuse and owns vulnerability in a way few public figures have ever thought to do. In an effort to understand unconditional love for the sake of his son, David Chang eats the peach. The effort is inspiring and courageous.

This article appears in Late Summer 2020 issue of Chanintr Living Download full issue

Or explore the entire library Visit the Chanintr Living Archive